A ‘great historical gangster play’ set light to the Caccia Studio last week, waking up audiences from their post-summer slumber with an unsettling and urgent message.

According to Director Ms Blake, the central message of The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui is that individuals “hold the power of choice,” particularly in resisting “abuses of power.” By choosing a satirical allegory of Hitler’s rise to power, she hoped “the audience would become critical observers” and “recognise the events unfolding before them in relation to the world we live in.”

Although this play has deep historical roots, comedy played an important role in reinforcing its message—it “creates a sense of detachment” and establishes that the audience is watching a performance. For example, after every death, cheerful music played and sometimes the characters even danced off stage. This was particularly important considering key moments of brutality, such as references to the rise of Nazism and an on-stage shooting. Despite this disconnection, the impact this play had was immediate and obvious, with members of the audience saying that they felt a “premonitory shiver” and a “real chill while watching evil.”

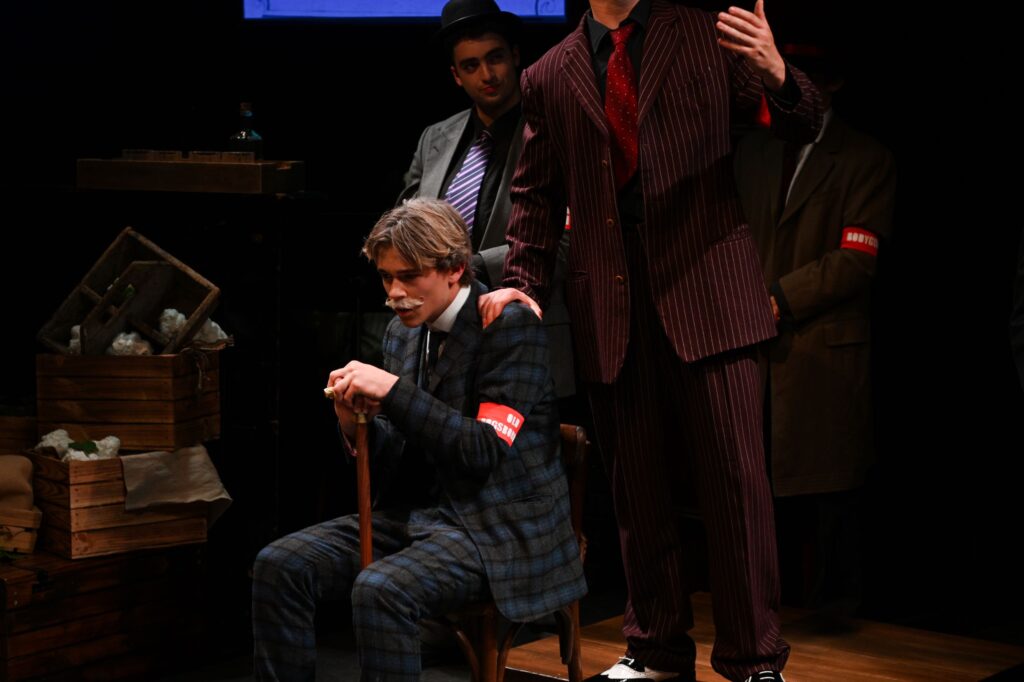

Set in Chicago during the Great Depression, the play began with a prologue. The Master of Ceremonies, played by Ben H, immediately broke the fourth wall and explosively introduced the main cast to the audience, aiming to remove any emotional connection with the characters. It is here that we met the leading figure of the gang who dramatically burst onto the stage at the drop of a curtain—Arturo Ui, based on Adolf Hitler and played with swaggering flamboyance by Roman B.

Throughout the play, Ui’s rapid germination of power and therefore confidence was powerfully presented to the audience—from a melancholic bitterness towards the ‘Cauliflower Trust’ (representing Prussian landowners) at the beginning to a terrifying overconfidence during his final speech at the rally, underpinned by sudden outbursts of anger or inspiration or both—elements which made the audience jump. The climax of the play was particularly unnerving because it seemed to leave the story open and unfinished. This, combined with the unstoppable crescendo of attention on Ui, eerily showed how easily a bad reputation can suddenly be forgotten by the crowd through manipulation.

A particularly farcical scene saw Ui receiving an acting lesson to prepare him for publicity. The Actor, also played by Ben H, received boisterous laughter from the audience for his melodramatic gestures of someone drowning in tragedy—he was praised for having one of the “most impressive” performances after the show. Caricatured movements didactically communicated that overconfident politicians cannot be trusted because they are primarily an image, manufactured to be appealing to the masses. Multiple spectators described how he reminded them of “demagogues” in the world today.

Yet, this play did not solely focus on the performative nature of politicians but also on the melodrama of the victim. The final scene before the interval saw A Wounded Woman (Ambrose B) alone on stage, despairingly calling out to the audience “Hey you!” for help as she clutched her bleeding wounds. An audience member described this as the “most memorable” scene—indeed, there was a tense silence in the theatre as the audience helplessly watched this character desperately begging for aid yet could do nothing but stare. When she finally died, the actor broke character and announced that it was the interval; another instance of a Brechtian technique that the Director said was “to interrupt the action.” It is very difficult to perform such an emotional scene convincingly, but for me and many others, it was truly a touching moment that burst with intensity and rawness.

Ui’s gang, consisting of Ernesto Roma (Wills N), aka Ernst Röhm, Giri (George M), aka Hermann Göring, and Givola (Francis W), aka Joseph Goebbels, were the source of the tension and infighting during the final parts of the play. The burning of the Warehouse, equivalent to the Reichstag Fire, and intricate plotting within the inner circle felt like an accumulation of disastrous events that were shockingly tied up in a final mass purge, or, as you may know it, the Night of the Long Knives.

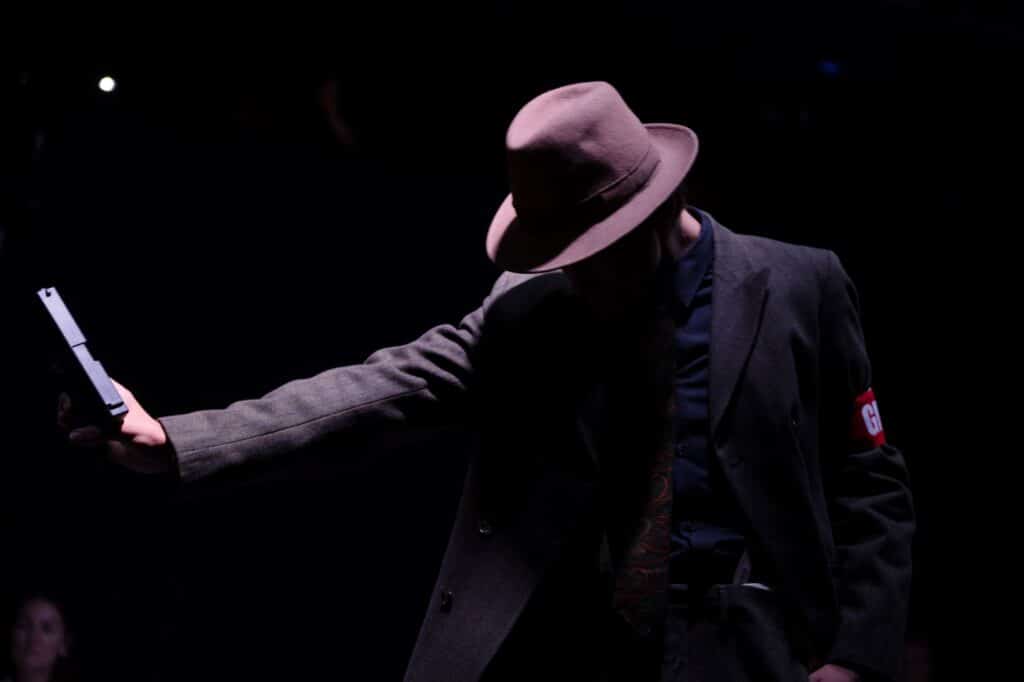

Roma, who had just believed Ui to be one of his closest friends, was abruptly shot, alongside all his men following after in a disturbing sequence. A member of the audience noticed how there was “genuine surprise in the faces of the audience.” Nobody saw it coming, especially Roma, who throughout the play, maintained a domineering presence on stage. He was the one with the gun and an unshakeable demeanour that even the audience feared. Yet, when cheerful Giri stole his hat (a souvenir he collects from everyone he kills) and Givola bitterly called him “crippled” before shooting him in the head, the audience still felt horror at the degradation of human life — demonstrating the actor’s ability to switch character both suddenly and seamlessly.

Although the ‘bad guys’ were central to the plot and overall message of the play, the ‘good guys’ also had many interesting internal struggles and were essential for the audience to draw comparisons with. In a way, there were no ‘good guys’ since nobody spoke out or stood up for what was wrong. Old Dogsborough (Senan W), representing Paul von Hindenburg, was the most obvious example of this, being the paragon of virtue that he used to be. However, his great reputation began to crumble when he accepted a bribe and allowed Ui to represent him, not before being punished with a spiralling series of unfortunate events. Throughout all this, Dogsborough’s descent both physically and emotionally was portrayed with clarity and conviction. His internal struggles on whether to speak out not only proved his cowardice but also asked the audience questions of their own inaction. This made an audience member reflect that “for evil to succeed, you need good men to do nothing.” Certainly, this was reemphasised when Ui broke character at the end to tell us to speak out and warn us that “the bitch that bore him is in heat again.”

Every design choice in this play was coherent with the plot and Brechtian techniques. The traverse stage itself was bare except for spike tape—all the set pieces were carried in by actors, and locations were signified by projected placards. Lighting was bare and sound was diegetic throughout except for in non-naturalistic moments such as dancing offstage to Life is a Bowl of Cherries after the mass murder. According to Ms. Blake, this was to make the audience “reflect rather than remain passive” and focus on the “political message of the play.”

Every character wore a red armband which said the name of their character—practically, this made sense due to the amount of multi-rolling. Further, if there was a quick change, it would happen on stage to make the audience fully aware of the characters and therefore the message they represented. Live musicians also played during the transitions and naturalistic scenes to give a sense of the period and atmosphere. One particular highlight was the massive puppet of the Judge (Raushan S) with his grey knitted wig that dropped down from above the stage. His giant papier-mâché hands took designer Mary Deakes two days to complete. This design choice cleverly conveyed how even the court was controlled by Ui. Altogether, it was a brilliant demonstration of the abilities and expertise of the Farrer Theatre crew—we can only look forward to what is to come as the year goes on.

Despite being written in the 1940s, the play is still topical and paints an alarming picture of how certain political figures today have remarkable similarities with the past. An anonymous spectator said that this play exemplifies how “new evil can prevail.” Similarly, another believed it to be “very pertinent, especially now.” The play’s success was not purely dependent on the writing. The direction was “done with great wit” and audience members were “very impressed with the American accents.”

Ms Blake and the boys of Durnford House should feel very proud of the lasting impact the play clearly made on the audience after each performance—perhaps even demonstrating that theatre can really change the world. Many congratulations to everyone involved!